Our canine friends are susceptible to a wide variety of health issues, with cancer unfortunately high among them. Of the many cancers, dog bone cancer, or osteosarcoma, is one of the most invasive and hardest to treat.

Osteosarcoma is an aggressive cancer that often spreads to other parts of a dog’s body. It is diagnosed in 8,000 to 10,000 dogs each year in the U.S., which accounts for roughly 85 percent of all canine bone tumors. Osteosarcoma is the most common primary bone tumor found in dogs. The cancer is so aggressive that it often requires amputation of the affected limb to provide respite from the disease.

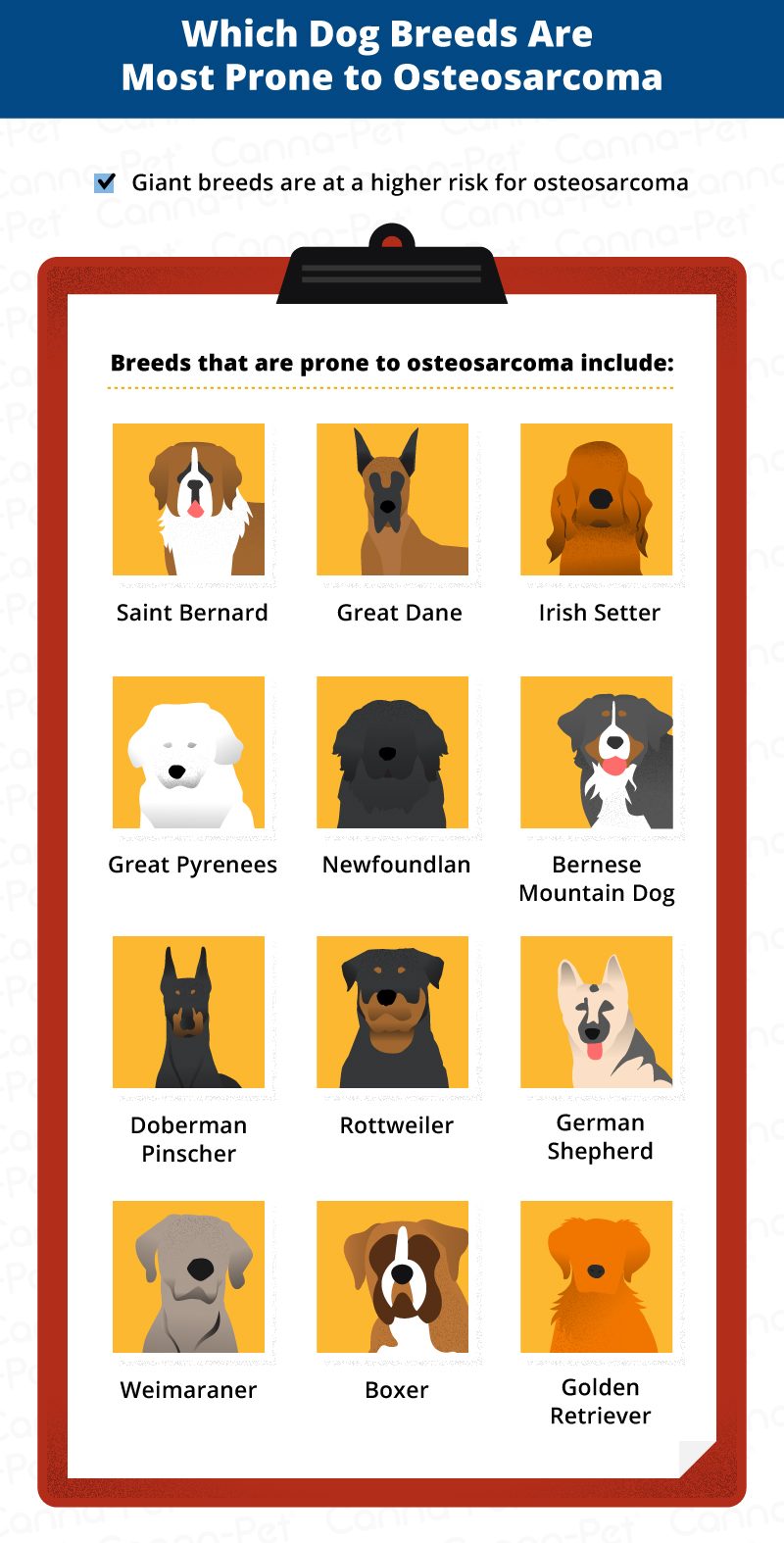

Which Dogs Are Most Susceptible to Osteosarcoma?

Big, older dogs are at highest risk for osteosarcoma.

Giant and large breeds have the highest propensity for the disease. Giant breeds most at risk for osteosarcoma include the Saint Bernard, Great Dane, Irish Setter, Great Pyrenees, Newfoundland, and Bernese Mountain Dog. Large breeds also found to be at an increased risk are the Doberman Pinscher, Rottweiler, German Shepherd, Weimaraner, Boxer, and Golden Retriever.

The overall average age for dogs to be diagnosed with osteosarcoma is around age eight. Large and giant breed dogs are diagnosed on average at age seven. Those dogs that receive a diagnosis of osteosarcoma in the ribs are typically four-and-a-half to five-and-a-half years old.

There are several environmental and genetic factors that can increase risk for osteosarcoma as well. The rapid growth scene in large and giant breed puppies makes them vulnerable to developing osteosarcomas. Male dogs are found to be at a 20 to 50 percent increased risk. Dogs that have a metallic implant used to repair a fracture may be at an increased risk as well.

While osteosarcoma does more commonly develop in older dogs, there is increased incidence of it occurring in one- to two-year-old dogs as well. Neutered and spayed dogs are found to be at higher risk as well.

Osteosarcoma does not often occur in small breed dogs. In fact, dogs under 30 pounds account for less than five percent of osteosarcoma cases. When it does occur in these dogs, the cancer typically affects the axial skeleton, which includes the bones of the skull, vertebral column, ribs, and sternum.

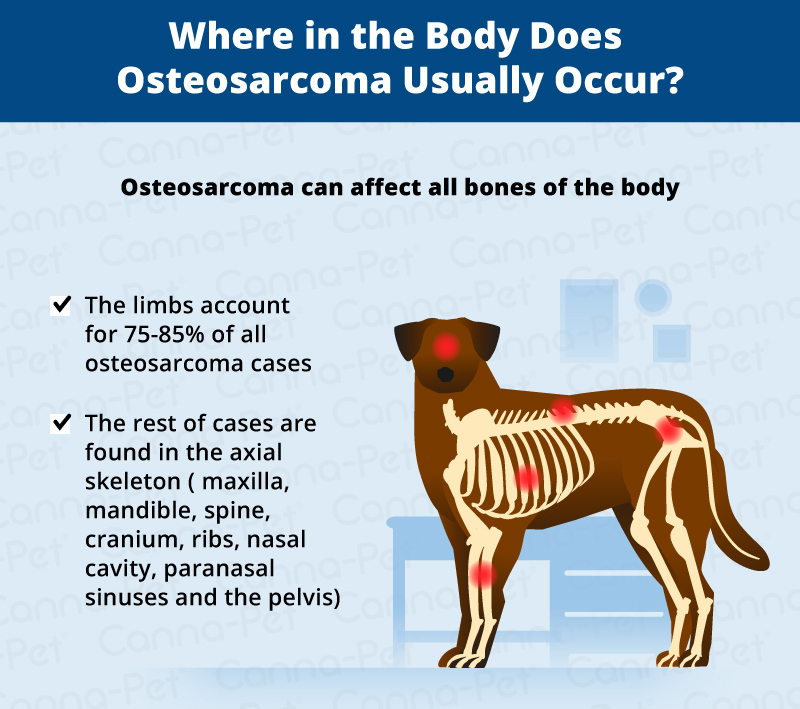

Where in the Body Does Osteosarcoma Most Often Occur?

While osteosarcoma can occur in any bone in a dog’s body, the limbs account for 75 to 85 percent of all affected bones. This is called ‘appendicular osteosarcoma’. Other cases are found in the axial skeleton, including the maxilla, mandible, spine, cranium, ribs, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and the pelvis.

In even more rare cases, the osteosarcoma can expand into the mammary tissue, subcutaneous tissue, spleen, intestines, liver, kidney, reproductive organs, eyes, ligaments, adrenal gland, synovium, and meninges. In these cases, the osteosarcoma develops deep within the bone and destroys the bone from inside. It becomes excruciatingly painful as it grows outward and affects the outside tissues.

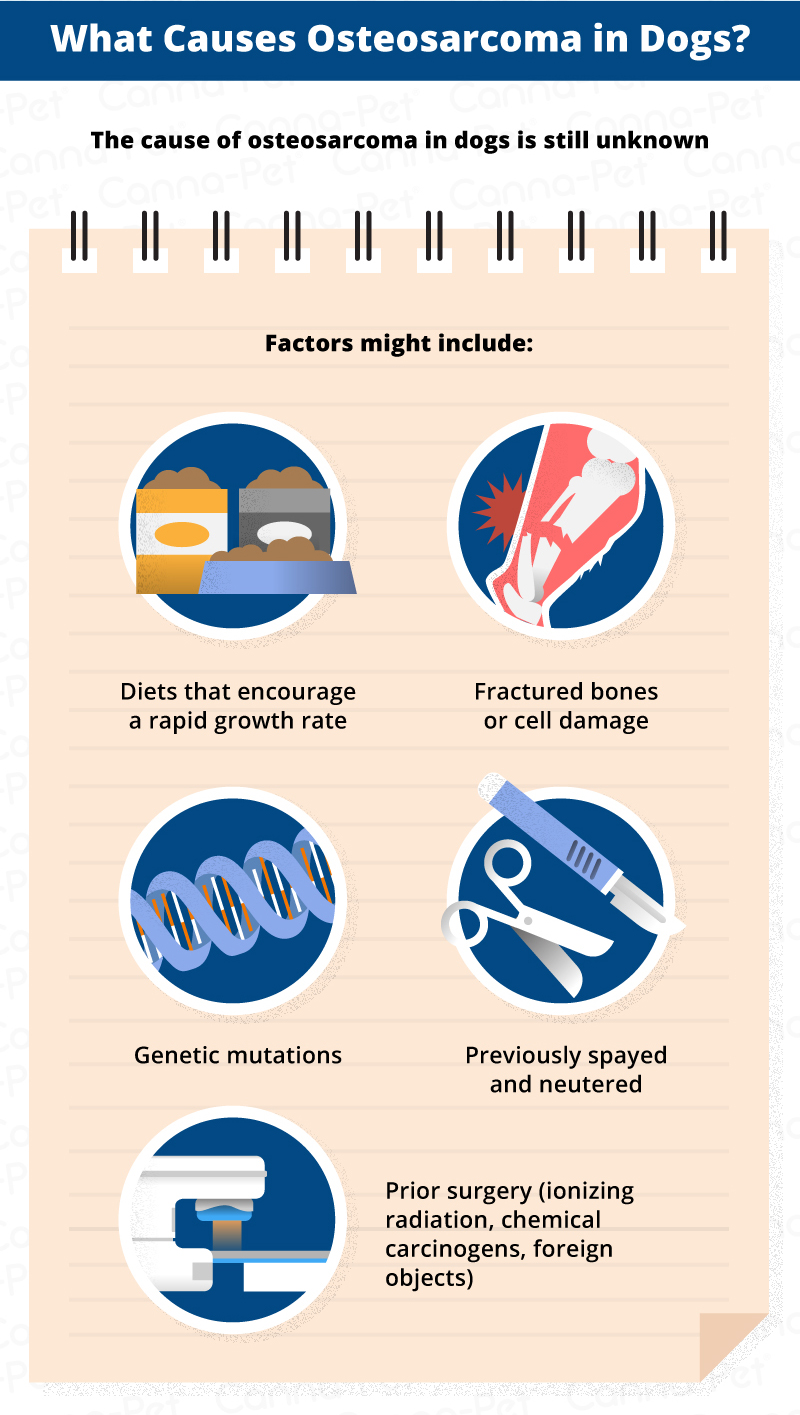

What Causes Osteosarcoma in Dogs?

Unfortunately, the cause of osteosarcoma in canines is not currently known. But there are several prevailing theories and factors that seem to be related to cancer signs in dogs.

Osteosarcoma tumors are frequently found near growth plates, so it has long been speculated that factors that affect growth rates, such as diets that promote rapid growth in puppies, influence their risk for cancer.

Dogs that have had fractures, mainly in their limbs, may be at a higher risk for bone cancer as well. Osteosarcomas appear to anchor themselves in areas of increased bone re-molding (which correlates with the theory on growth plates). Where there is cell damage or increased turnover, the DNA is more likely to make a mistake when coding new cells, which can lead to the formation of a tumor. This particularly affects the forelimbs, which bear most of a dog’s body weight.

Dogs that have had surgeries may be at higher risk at well. Things like ionizing radiation, chemical carcinogens, foreign bodies inserted during surgeries, such as metal implants like internal fixators, bullets, and even bone transplants can contribute to the development of osteosarcoma. The disease has even been associated with chronic osteomyelitis and in fractures where no foreign bodies were used in repair.

There are also genetic factors that appear to be involved in the development of tumors. Certain family lines can be more genetically predisposed than others to osteosarcoma. Dogs with osteosarcoma have also been found to have aberrations of the p53 tumor suppressor gene. In laboratory animals, both DNA viruses (polyomavirus and SV-40 virus) and RNA viruses (type C retroviruses) have been found to induce osteosarcoma.

There is also evidence to suggest dogs that have been spayed or neutered at an increased risk of developing bone cancer.

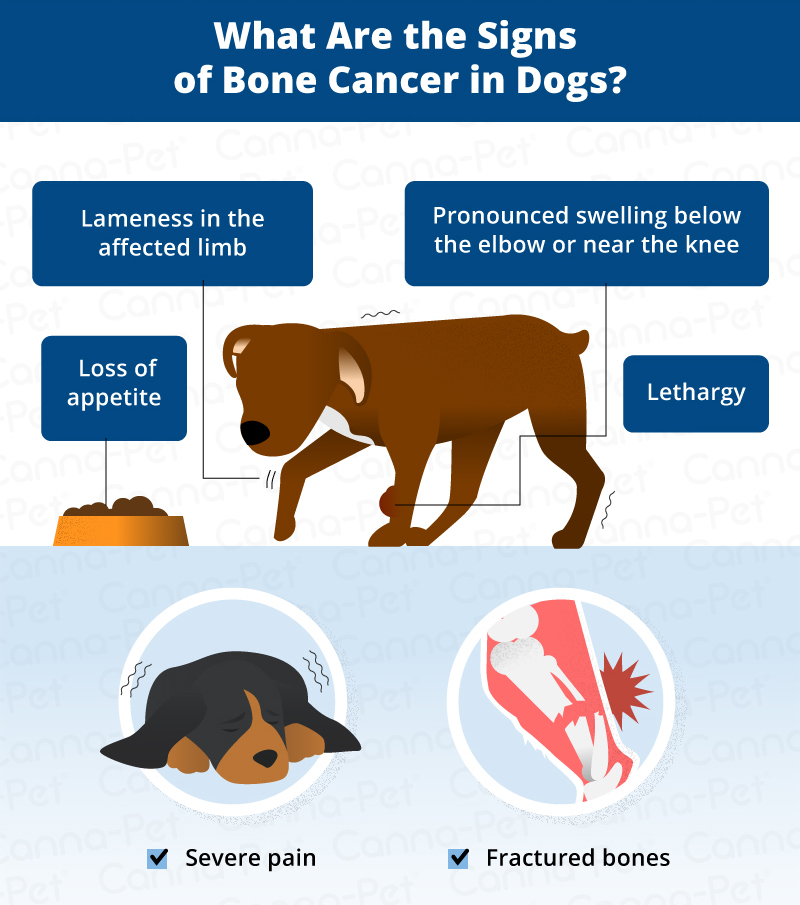

What Are the Signs of Bone Cancer in Dogs?

While symptoms of bone cancer may be difficult to notice in your pup, there are some signs you can look for.

Since most osteosarcomas develop in a dog’s limbs, the places you will most often find signs are below the elbow or near the knee. As the tumors usually form at or near growth plates, dogs affected by osteosarcoma will often have pronounced swelling in these areas. The swelling will cause your dog some discomfort, which is often first detected by lameness in the affected limb.

If the osteosarcoma is in another part of the body other than it’s limbs, symptoms will depend on the location. For example, if the cancer is in the jawbone, your pup will have difficulty opening its mouth or eating. Your dog also might become increasingly lethargic and/or lose its appetite.

Bones with osteosarcoma aren’t as strong as normal bones, so even a minor injury can cause a fracture. Sometimes the first sign that osteosarcoma is present may be a fracture at the site of the tumor.

As the disease progresses, the tumor will grow and gradually deteriorate the bone. This will make life more painful for your dog and the intermittent lameness will become more frequent, until it is constant. This usually occurs within one to three months of the onset of the tumor.

How is Osteosarcoma Diagnosed?

Osteosarcoma can be difficult to diagnose. X-rays and histopathology (an examination of tissue) are the primary diagnostic tests for osteosarcoma. Osteosarcomas have a lytic, or “moth-eaten” appearance on X-rays that is characteristic of the tumors.

In addition, blood tests and chest X-rays are usually performed to check for additional lesions and underlying medical conditions. Coupled with history and breed, X-rays will often reveal a characteristic bone pattern that may indicate the development of an osteosarcoma. Up to 90 percent of these tumors will have spread to the lungs by the time an osteosarcoma is diagnosed, but because the initial metastases are so small, less than 10 percent will initially show up on a chest X-ray.

Because of this high incidence of metastasis in the lungs, all dogs with osteosarcomas are treated as if they have metastasis regardless of whether or not the initial lung X-rays found any signs. This metastasis of the osteosarcoma to the lungs or other organs is the most common cause of death in dogs with this tumor.

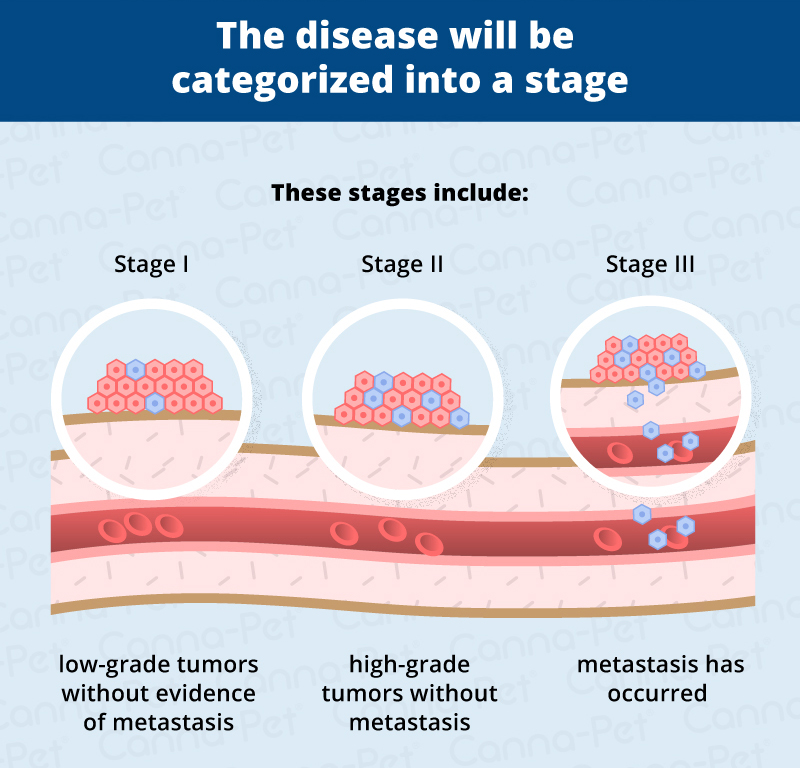

The disease will also be categorized into a stage. These include:

- Stage I – low-grade tumors without evidence of metastasis

- Stage II – high-grade tumors without metastasis

- Stage III – metastasis has occurred

Since osteosarcomas can occasionally show up at different locations in your dog’s body, they can sometimes initially appear to be other forms of cancer or tumors. Likewise, other tumors can appear at first to be an osteosarcoma.

Fungal bone infections can also produce similar symptoms and appearance on an X-ray. Because of these possibilities, a biopsy is recommended to eliminate any uncertainty, and an additional fungal culture may be performed to further clarify the diagnosis.

Blood tests for total alkaline phosphatase and bone alkaline phosphatase may be conducted prior to surgery to provide information as to the prognosis. In general, the higher the values, the poorer the diagnosis.

Treatment for Dogs with Osteosarcoma

Because osteosarcoma is such an aggressive, highly metastatic cancer, it requires an equally intensive treatment protocol.

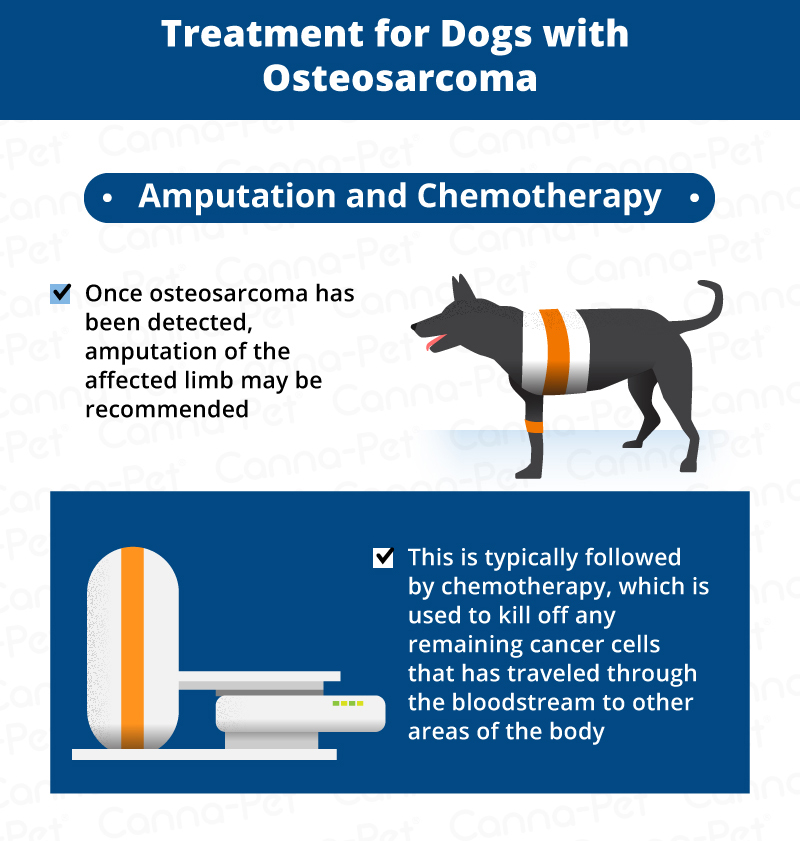

Amputation and Chemotherapy

After the tests and X-rays have been conducted and a tumor has been positively identified as an osteosarcoma, the most common course of action is an amputation of the affected limb. This generally results in the total removal of the disease.

This is typically followed by a course of chemotherapy to catch any stray cancer cells that may have already traveled through the blood to other areas. Chemo is only given in cases where the primary tumor has been surgically removed. It is totally ineffective on dogs that aren’t candidates for surgery.

The standard protocol is four to six treatments, three weeks apart, but refer to your qualified veterinary oncologist as he or she will be aware of the newest chemotherapy protocols.

Limb-Sparing Surgery

The limb may be spared in rare cases where the tumor is small and in the right location, but this is rare. However, in this surgery, the affected bone is removed and replaced with a bone graft or a combination of bone graft and metal implant. Candidates for this surgery include otherwise healthy dogs whose primary tumors are confined only to the bone.

This risky procedure comes with potential complications, including the development of infection, recurrence of the tumor, and failure of the bone graft to “take”. This occurs in about 10 percent of cases. This procedure is also typically followed by chemotherapy treatment.

With this surgery, there is little chance for recurrence because an absorbable chemotherapy (cisplatin) sponge is inserted into the wound during the operation. This sponge reduces the chances of local recurrence.

The sponge is a biodegradable polymer, which slowly breaks down in the body, releasing cisplatin in very high concentrations to the tissues in the surgery site. This high local dose of cisplatin will kill the remaining cancer cells in the leg. Only a low dose enters the bloodstream.

Radiation Therapy

Osteosarcomas are very painful, so if the limb is not amputated, therapies to relieve the pain should be administered. Radiation therapy may be prescribed. The treatment does not significantly affect the progression of the disease, but will greatly improve the quality of life in many dogs.

Radiation doses can be applied to the tumor in three doses. The first two doses are given one week apart, the second two, three weeks apart. The treatment will often improve limb function with the first three weeks and last up to four months. If the pain returns, radiation can be re-administered if it is the appropriate course of action based on the stage of the cancer at that time.

Improving Quality of Life

In more advanced cases, owners may choose not to pursue amputation and instead focus on relieving pain and giving their pets the best quality of life for the time they have left. This can include radiation as well as natural supplements to alleviate any pain.

For those who choose a naturopathic route of treatment, injectable forms of vitamins A and D, bromelain, omega-3 fatty acids, and a blend of herbs called the Hoxsey Formula with boneset are often prescribed to help alleviate symptoms. This is often coupled with eliminating all processed foods and reducing carbohydrate intake.

What is the Prognosis for Dogs with Osteosarcoma?

The prognosis for dogs with osteosarcoma varies and depends on several factors.

For those that are treated with amputation surgery and chemotherapy, about 50 percent achieve a survival rate of approximately one year. However, some dogs have actually survived 5 to 6 years.

Dogs with large tumors that receive radiation treatment have an average survival rate of seven months. For those dogs that have axial osteosarcoma (found in another area of the body other than the limbs), the survival rate is much lower because complete surgery is not possible.

Periodic follow-up will be necessary to monitor a dog’s progress

Is Osteosarcoma in Dogs Preventable?

Currently, osteosarcoma is not preventable. But because there are strong correlations to some breeds, any breed line that has a history of osteosarcoma should be examined closely prior to breeding.

Full Infographic

Sources:

- “Bone Cancer (Osteosarcoma) in Dogs.” PetMD, Accessed 3 Dec. 2016. www.petmd.com/dog/conditions/musculoskeletal/c_multi_osteosarcoma.

- “Osteosarcoma: Bone Cancer in Dogs.” Pet Health Network, Accessed 3 Dec. 2016. www.pethealthnetwork.com/dog-health/dog-diseases-conditions-a-z/osteosarcoma-bone-cancer-dogs.

- “Dogs at Highest Risk for Osteosarcoma Bone Cancer.” Healthy Pets, Accessed 3 Dec. 2016. www.healthypets.mercola.com/sites/healthypets/archive/2015/08/02/osteosarcoma-dogs.aspx.

- “Treatment & Prognosis for Bone Cancer (Osteosarcoma) in Dogs.” Petwave, 16 July 2015, Accessed 3 Dec. 2016. www.petwave.com/Dogs/Health/Osteosarcoma/Treatment.aspx.

- “Osteosarcoma.” Canine Cancer, Accessed 3 Dec. 2016. www.caninecancer.com/osteosarcoma/.